Who Deserves Mercy?

Jonah 1:1-17; 3:1-10, 4:1-11

Jonah is a familiar story. One where if we have heard it too many times we forget its main purpose. We know in the ending that Nineveh repents and Jonah is a whiny baby. But what I would like us to do is pretend we are reading this story for the first time. Jonah is a prophet of God. This is a designation where the audience would immediately know that he is the protagonist and hero of the story.

God tells him, “Get up and go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it, for their evil has come to my attention.”

And now the audience starts to get ready for a sweet revenge story where the God of justice finally metes out divine punishment to the wicked and long time antagonist of the story of ancient Israel. Nineveh is the capital of Assyria. The long standing oppressor of ancient Israel. These are the people who have tortured them, kidnapped them, and desecrated their holy places. Nineveh is clearly the bad guys. Everyone knows this.

So we start this story. Jonah is the good guy with divine power from God and Nineveh are the bad guys who deserve whatever is coming to them. Like Egypt’s warriors drowning in the Red Sea, the audience is ready for this action packed story of sweet sweet vengeance.

But this story, it turns out, is not an action thriller. No. It is in fact a comedy. A comedy that uses the audience’s expected understanding of hero and villain and flips the script on its head. Verse 3, Jonah got up, the audience assumes to go on this holy mission of God, but instead Jonah immediately and without a single word flees the opposite direction. The audience wonders, “What? The protagonist is running away? The hero is fleeing his responsibility? The good guy is doing the opposite of what God commands?”

“Okay,” the audience thinks, “maybe this was just the learning opportunity to trust God. Jonah will get it right on the second try. Every good story needs a failure before a success.” Jonah is tossed from the boat. Interesting enough, Jonah doesn’t suggest turning the boat around but still tries to get out of his responsibility with his death. God surprises again and has him swallowed and then vomitted near Nineveh by a fish. “Okay,” the audience starts to skeptically hope, “so maybe this is a reluctant prophet who is scared of the Ninevites and will learn to trust God and see God’s justice on Nineveh.”

But sadly we then we see Jonah do the bare minimum. The text says that the city of Nineveh would take three days to walk across. So Jonah walks in for half a day. Delivers the exact words God has told him to say, no more and no less. “Just forty days more and Nineveh will be overthrown!” Then Jonah leaves the town to go sit on a hill and watch the impending destruction. Jonah was finally faithful. Jonah showed up, albeit reluctantly, to deliver his message. Now the audience finally gets to see the protagonist win and the antagonist lose. We settle back into our chairs. All is right with the world. The good guy wins and the bad guy loses.

Right?

But no. What’s this? The people completely repent. From the king to the stablehand and even the animals. They all commit to change their ways. They fast and wear sackcloth, even the animals to show their repentance. This is not how bad guys act. Bad guys don’t say they are sorry. Bad guys don’t get forgiven. Bad guys need to pay! But God changes God’s mind (a whole sermon for another day) and the people are saved.

Jonah is furious. Jonah throws a fit complaining that it would be better for him to die than to see his enemies repent and change and receive mercy. It would be better to die than to see God’s mercy for someone who is bad. (How many of the audience, how many of us, might feel something similar?) God finally steps in and ends the narrative with a question that seems to have a clear answer but makes us question our roles in this narrative. “Can’t I have mercy on Nineveh?”

How are we to hear this story today? The author wants us to think we are the protagonist like Jonah except that it turns out Jonah is the one who does not understand God’s mercy, when everyone else gets it. The people on the ship, the Ninevites, and even the animals!

At One Parish One Prisoner, we see this story play out all the time. Churches and religious people believe we are the protagonists and that God is only on our side and not on someone else’s side. We are comfortable with the distance between us and them. That feared “other” who makes us uncomfortable. And nowhere does this line show up more clearly in our society than with people coming home from prison.

When someone comes into a nice church where people are well dressed and well groomed but this stranger has tattoos on their face and is wearing a tank top, our immediate thoughts might ring more like Jonah than like God. “Maybe I should flee…”

At one of our first One Parish One Prisoner churches back in 2017, we had a nice Presbyterian church that was meeting inside a cool venue and even had a hip coffee shop to serve the downtown Seattle Amazonian crowd. When we paired them with a former member of the notorious MS13 gang, ever heard of it, the optics of our culture could not have been clearer about who the supposed good guys were and who the bad guy was.

But the church that day understood what God was showing us in this story. Angelo, name changed, was simply another human being. It was not that his past was squeaky clean or that he had never caused harm. But it was also not something that God was unwilling to forgive and offer a new chance. These two groups from completely separate backgrounds came together and built a relationship of mutuality and radical solidarity. The harm and sins of Angelo that he could not easily hide opened up the vulnerability of those church members to share about their struggles with mental health or addiction.

Jonah has the opportunity to be transformed in relationship with the Ninevites in this story. Jonah hides and runs and does the bare minimum, eager to avoid this “merciful and compassionate God, very patient, full of faithful love, and willing not to destroy.” It begs the question of us. How will we respond to God’s call to move closer to the other? To open ourselves up to new relationships that might feel uncomfortable?

We so often see ourselves as the protagonist in our stories. The author of Jonah uses that inclination to shatter the binaries of our world. Who is in or out? Who is good or bad? Who deserves God’s mercy or not? These binaries restrict our worldview and our ability to see and receive mercy in our own lives. Because Jonah not only tried to restrict the mercy for Nineveh but he rejected it for himself.

At One Parish One Prisoner we ask the question, what would happen if Jonah had gotten to know the Ninevites instead of prejudging them and assuming they would always choose destruction? In our work, we build relationships between the incarcerated and the communities to which they return. We build a team of 7-10 people in each church, train them on how to build a relationship, and launch them on a two year journey of mutual discovery, embrace, and trust. How might a relationship with someone who society says is so different from us actually open us up to see more grace and mercy in our own lives?

While Jonah did the bare minimum that God asked, keeping his distance, and avoiding the Ninevites to the best of his ability, God asks who deserves mercy? How will we answer this question? Will we run away from God’s call to share mercy? Will we reject the mercy offered to ourselves in this process? Will we cling to our binary understanding of good and bad? Or will we open ourselves to the binary-breaking mercy of a God whose love is overflowing?

This story is not actually about Nineveh. We can insert all sorts of enemies into this good guy/bad guy narrative. But this story is called Jonah. It is about Jonah. It is about those of us who think we are the protagonist and is a challenge to us to consider who we prejudge and how we might open ourselves up to God’s mercy in relationship with someone we have deemed irredeemable. How might we be transformed? So let the story of Jonah turn us inward to receive mercy so that we can go out and create a world filled with this mercy.

May we go and make it so.

—

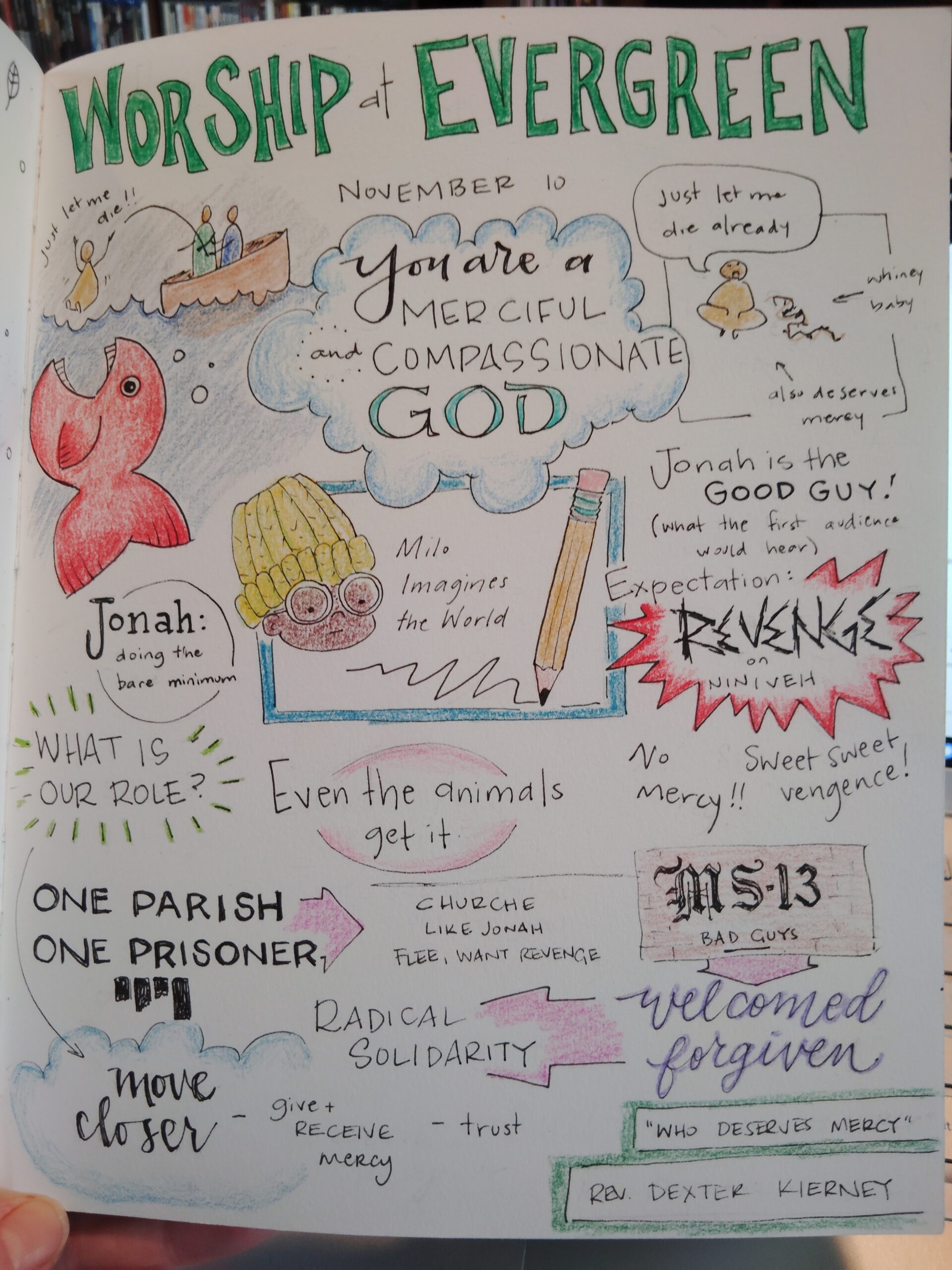

image art: sketchbook page by pastor amy of notes taken during worship

—