Faithful Table Turning

Text: Genesis 38:1-26 (included in audio)

This story was not among the scriptures I memorized in Sunday school, and we were not asked about it in any of the Bible quizzing tournaments of my youth. I have no recollection of ever hearing it read and preached on during a Sunday morning service. On the whole, the church tends to avoid Bible stories like this one.

We might avoid it because it makes us uncomfortable with its sexual imagery and its focus on bodies—bodies that release fluids and bodies that can become pregnant and birth babies. We might avoid it because of the shocking decision of Tamar to intentionally use her body in the unsettling and exposing way that she does.

We might avoid this story because it invites us to contend with uncomfortable moral and ethical questions. We might avoid this story because some part of us is aware that it doesn’t just reflect archaic patriarchal customs of an ancient people; it exposes something about our own lives, our own time and place.

As we meet this story, perhaps for the first time, it is vital that we center Tamar—her perspective, her choices, her courage and resilience—because that is precisely what the author of this story does. Tamar emerges here as the character who is identified as most righteous and faithful to the unfolding work of God. She becomes a faithful table-turner.

“Turning the tables” is a familiar idiom we use to describe a reversal of fortunes, to reverse one’s position relative to someone else, sometimes in favor of a disadvantaged party. As a Christian, when I hear the phrase, I think immediately of Jesus turning the tables in the Jerusalem Temple. An appropriate image, but not the origin of the phrase “turning the tables.” Does anyone know where it comes from?

Backgammon. The phrase comes from the ancient Mesopotamian game of backgammon, and the practice of sometimes turning the board so that players must play their opponent’s pieces.

Tamar is a faithful, though decidedly unconventional, table turner.

To understand what that means we need some context for this story that really appears out of nowhere in the narrative flow of Genesis. In the preceding chapter, Genesis 37, we are told of a young Joseph being sold into slavery by his eleven brothers, including Judah. Joseph’s story is picked up again in chapter 39. Sandwiched in between is this narrative that follows years of Judah’s life in the land of Canaan.

Another important part of the context of this story is the practice of levirate marriage. In levirate marriage, the brother of a deceased man is expected to marry his brother’s widow. In the Jewish law it is described in Deuteronomy 25:5-10. There, it further states that when a man marries his brother’s widow, the firstborn child of that marriage will actually bear the name of the deceased brother—as if it is actually the dead brother’s child. This, in effect, maintains the deceased brother’s family line in the world. It was a way of maintaining lineage, familial power and control in a patrilineal society.

It is also important to our reading of this story to remember that levirate marriage, when properly practiced, afforded some amount of protection to a widow. The widow retained social status within the family as she married the other brother, rather than being left on the vulnerable margins as an unmarried widow. In this story, however, levirate marriage is not properly practiced, and it leaves Tamar in the most vulnerable position of all.

A brief summary:

Judah has settled in the land of Canaan and marries Shua, a Canaanite woman

Judah and Shua have three sons: Er, Onan and Shelah

We learn that Judah “took a wife” for Er: Tamar (presumably, Tamar is Canaanite)

In very abrupt narration we learn that Er was wicked in the Lord’s sight and the Lord puts him to death (a theologically problematic storyline to be sure!).

Following levirate marriage practice, Tamar is married to Onan.

Things are going according to the law until Onan decides that he does not want to bear a child with Tamar and appears to practice the ancient form of birth control known as coitus interruptus. Onan’s act is a form of trickery and deceit (the stories of Genesis are full of trickery and counter-trickery).

In this case, God is clearly not happy with Onan’s trickery and Onan is put to death (God’s patience is clearly wearing thin!).

At this point, having now lost two sons, Judah comes to Tamar and says, “Go and remain a widow in your own father’s house until my son Shelah gets a bit older.” This is what he says, but the narrator of our story tells us what he is really thinking: Judah is fearful. In his own deep grief, Judah is afraid of losing a third son. So, with his own bit of trickery and deception, he sends Tamar off to her family home, with no intention to welcome her back as the wife of his third son.

Verse 12 begins “In the course of time…” and we can presume that years have now passed. Tamar has been relegated to live as a widow in her family home. It has no doubt become clear to her that Judah has no plan for her to marry his youngest son. And this is when Tamar chooses to act. The men in this story, Judah in particular, out of their fear and desire to maintain control and power, have chosen a path of inaction and separation. Tamar chooses to act, to reconnect, and engage. She proceeds with boldness and courage, using the resources available to her: her wits, her will, and her body.

Clothing becomes important here (we might recall Jacob dressing up like Esau to claim the birthright, or we might think of Joseph being cloaked in the colorful robe by Jacob) as Tamar removes the garments of a widow and veils herself in disguise. Whether she intends to dress the part of a prostitute it is not clear, but it is clear that this is who Judah presumes her to be when he sees her at the gates of the city and propositions her.

Tamar is calculated and asks for a commitment from Judah to prove he is good for his promised payment in exchange for sexual relations. She asks him to leave his signet and cord, the equivalent of leaving your photo ID with someone. The text is full of euphemisms at this point to let us know that the two have intercourse and that their tryst leads to Tamar’s pregnancy.

Months pass, but finally the revealing moment comes when a nosy neighbor comes to Judah and says: “Did you know that Tamar, your widowed, unmarried daughter-in-law whom you sent back to her home is now pregnant?” Judah is incensed and now he seems fully prepared to follow the letter of the law and have Tamar put to death.

This is the moment the tables are turned, the game is flipped, and secrets are exposed. Tamar reveals the signet and the cord of Judah and identifies him as the father of the twins she is carrying.

This is the most vulnerable moment for Tamar and it could have ended very badly for her, as it has for countless women in history who have boldly exposed the sins of powerful men. But, it doesn’t. Exposed for his negligence, his abuses and deceptions, Judah responds, “She is right,” The Hebrew word he uses is tsadik, or “righteous.” Judah says, “She has been more righteous in this matter than I.”

The term tsadik speaks of being faithful to relationships. Judah is saying that Tamar has been more faithful and has done greater justice to the bonds of their relationship through her action than he has through his inaction and negligence. Faithful not only to herself and to his family, but the word implies that she has been righteous and faithful to God. In the face of Tamar’s truth-telling, Judah repents.

The story concludes rather quickly with the account of the twins’ birth, Perez and Zerah. And as the stories of the Hebrew scriptures continue to unfold, we discover that Tamar and her children become part of the ancestry of King David and then, in turn, part of the lineage of Jesus.

Quite a story! Does it seem strange, ancient, distant? I mean, we don’t practice levirate marriage anymore. Widows and widowers are free to remarry as they desire. We live in completely different times now, right?

Or, do we hear echoes resounding in our own times? How much have we evolved beyond the painful dynamics present in this story? What do we witness in our world today? We certainly see leaders, much like Judah, who are deeply wounded and profoundly flawed—the vast majority of them men—who build and fortify their power and control through fear, deceit, inaction, secrets, negligence, violence and more.

We live and move in systems and structures that remain patriarchal to their core, that are built on a potent latticework of sexism, racism, homophobia, and social and economic stratification. These leaders and systems benefit from separation—keeping people apart and siloed—and utilize fear to maintain division.

The church has been woven into these systems, and the persistent ills of patriarchy have been woven into the church to this day. We can readily point to the ways nationalism and fundamentalism have deformed the church into expressions that seem such a far cry from the Gospel message—so far as to be unrecognizable. And it is also true that we can just as readily point the fingers towards our own selves, our own beloved church structures and institutions, and see the ways power and authority have been maintained by some at the expense and neglect of others, how some leaders have willingly deceived and abused others, and how seats of power and leadership are not yet fully accessible to all.

Carl Jung once remarked, “Where the will to power is dominant, love will be lacking.”

The “will to power” is alive and well in our society at this moment. And love can seem terribly, painfully lacking. I’m not speaking here of love as something sweet, warm and fuzzy, but rather love that is creative, enduring and courageous—fiercely so—and love that speaks truth to powers and principalities. In other words, Gospel love. Love like Tamar’s.

The word “love” never appears in Genesis 38, yet, I sense it is a dominant force—particularly active through Tamar—as she thwarts the powers of fear and separation and makes a way for herself and others back into connection. Tamar’s love makes a way out of deception and into truth. I will close by naming two particular challenges that I believe we are invited to take to heart as we encounter Tamar’s story:

1) The heart of justice building, and a necessary ingredient in the way of love, is TRUTH-TELLING. God can only love and work within what is most true and real. Deception, lies, “fake news” is all about manipulation and control.

Love works only within what is real and true. Our widespread cultural acceptance of lying is a primary reason many of us will never know love. It is impossible to nurture one’s own or another’s spiritual growth when the core of one’s being and identity is shrouded in secrecy and lies. Trusting that another person always intends your good, having a core foundation of loving practice, cannot exist within a context of deception.

– bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (p,46)

Another way this gets reframed in the gospel: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Love is an active force and we see this in Tamar. Her actions reveal a love for herself and for the wellbeing of others, including Judah. Her actions are liberative not just for her but for the family system that has neglected and abused her. You and I, on the path of faith and in our commitment to the community of faith, are called to truth-telling, including confronting the

lies and deceptions of our times and speaking truth to power.

2) God is present and at work in and through our lives and we cannot presume our life, or any life, is insignificant or unimportant. You might have noticed that God isn’t mentioned much at all in Genesis 38. Yet, similar to the rest of Genesis, there is an underlying implication that God’s vision and dream is somehow finding expression through lots of very strange, fallible and unlikely people. It’s finding expression through Tamar.

The story [of Genesis] is told in such a way that makes every one of these lives seem absolutely consequential . . .God’s humanism is so absolute that one particular Egyptian serving girl [Hagar] must be the mother of the Ishmaelites, one particular Canaanite widow [Tamar] must complete in long anticipation the genealogy of King David. By extension, any one of us, if we knew as we are known, would realize that there was a role that required our assuming it, uniquely, out of all the brilliant constellations of human families.

Marilynne Robinson, Reading Genesis, pp.226-227

If we knew as we are known…what a wonderful, soulful phrase. If we knew ourselves as we are known by God, we would see most clearly the precious value of our lives and the unique roles we are called to fulfill out of love for God, love for ourselves, love for our neighbors, and love for this broken, beautiful world. Amen

—

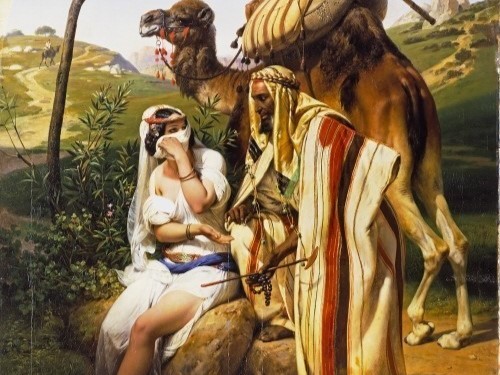

Image: Emile Jean Horace Vernet