God and the Other Woman

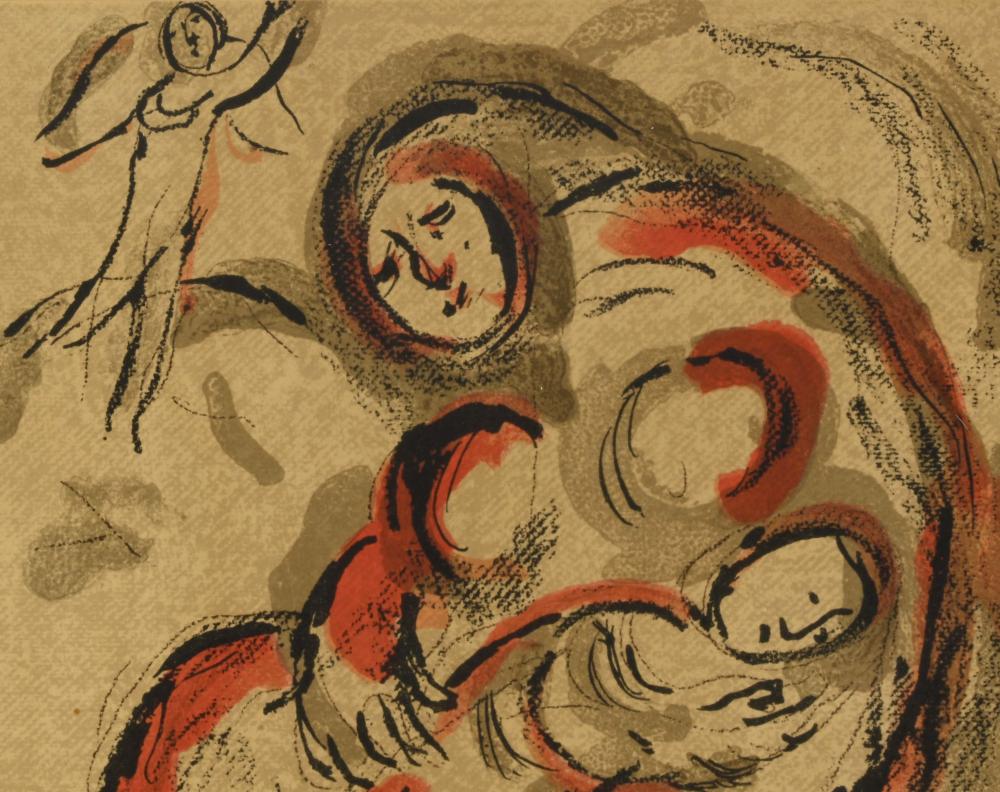

Image: Chagall, “Hagar in the Dessert”

Text: Genesis 16:1–16; Genesis 21:8–21

If you read the e-Memo this week you’ll already know that in and among other things that are going on this summer, we’ll be looking at the stories of women in the Hebrew Bible – aka the Old Testament. You’ll also already know that the Bible contains some ‘not-safe-for-work’ content. At the very least, most of these stories that we’ll be reading together this summer rise to night-time soap-opera level drama and intrigue.

Some of the threads of this story today did literally weave their way into a popular streaming series. I didn’t watch “The Handmaid’s Tale” when it was so popular, but I have read the book by Margaret Atwood. Most recently I discovered it as a graphic novel. In the novel – and I assume the streaming series – wealthy women who are unable to bear children use the bodies of handmaids as surrogates, bringing them ritually into their marriage beds to conceive.

One of the things that I appreciate about Margaret Atwood’s book is that it is told from the viewpoint of the handmaid. From the woman who has no name but the name of her master. Whose body is not her own. Culturally we’re usually predisposed to dislike and disdain the ‘other woman.’ These are women who break up marriages, who break up bands, who lead to the downfall of what is good and right.

But culturally in the time of the Hebrew Bible, it was apparently not uncommon to have surrogates in this way and among the patriarchs there are multiple stories of families including ‘other women.’ In fact in the Hebrew Bible there are many stories of God working alongside, ‘the other woman’ to bring blessing.

I don’t love the way Sarah acts in this story. Driving her young, pregnant slave girl into the desert not once, but twice (well, the second time it’s the woman and her child) it’s not a good look. Sarah is the one with a spouse, with wealth and resources, with God’s explicit blessing. And yet that’s what puts her in the position she’s in, where she begins to feel desperate. She’s heard God’s promise and can’t possibly see how it would come to pass. She needs to take things into her own hands!

The problem is, taking the situation into her own hands doesn’t mean fertilizing eggs in a test tube and paying a person recruited by the fertility clinic to carry her baby. It means forcing a sexual relationship between a young enslaved woman and her husband. It’s no wonder Sarah would feel anger and jealousy when Hagar becomes pregnant, or threatened when she finally has a child of her own. Hagar, meanwhile, has no power, no agency and no protection.

Sarah lashes out at Abraham when she’s experiencing these feelings of anger and jealousy, saying, “It’s all your fault!” Immediately followed by, “I allowed you to embrace my servant.” But they’re both – they’re all – in a terrible position. Last week, Kathryn quoted trans writer and activist Schuyler Bailar, who said, “The problem is not cis/straight men, the problem is patriarchy.”

It’s true now and it’s true of the patriarchs themselves! The problem is not Abraham, or even Sarah, though she was the one to take action. The problem is the expectations of a culture and families that look a particular way – and Hagar gets caught at the intersection of all of it.

Thirty odd years ago Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality’ to describe that experience. By now many people have heard of this idea – the idea that a person or group’s individual and social identities combine or intersect to contribute to unique experiences of discrimination or privilege. Crenshaw’s work emerged as a way to describe both the sexism and anti-black racism experienced by black women.

Hagar didn’t have the word but she had the experience. She sat at the intersection of being enslaved, a woman – almost a girl when the story begins, and an immigrant. For this reason, he story has resonated with Black women for centuries. Around the same time that Crenshaw published her first work about intersectionality, Delores William, a bible scholar was beginning to write about Hagar’s story aligning with the experiences of Black women.

Williams says, in the introduction to her book Sisters in the Wilderness,

Even today, most of Hagar’s situation is congruent with many African-American women’s predicaments of poverty, sexual and economic exploitation, surrogacy, domestic violence, homelessness, rape, motherhood, single-parenting, ethnicity and meetings with God. (p 5)

That is an astonishing sentence. The list of experiences of oppression and it culminates with encountering God. Hagar is driven into the wilderness twice. And twice she has profound experiences with God when she is most in crisis.

In the first instance, when Hagar is pregnant and hopeless, she has run away from what seems like an impossible situation. God finds her and what I want to happen in this story is for Hagar to find liberation. I want God to release her from the oppression of being ground down. I want her to have autonomy and resources. Instead God tells her to go back.

But I’m going to back up just a smidge. In the context of this story, it might have been astonishing to Sarah and Abraham that God appears to Hagar at all. A slave. A foreigner. And not only appears to Hagar but receives a name unique to their interaction. Hagar is the only person in the Bible given the power to name God. They have a kind of face-to-face encounter in which Hagar is fully seen in the wholeness of herself and so calls God, “El Roi,” God who sees.

God sees and God also blesses. Another astonishing turn. Hagar receives the same kind of blessing that Abraham received. Even Sarah has not yet had her own encounter with the divine. But Hagar receives an assurance that she will be the mother to so many they will not be counted.

But God tells her to go back! To go back! God tells her to go back and in the first It must have been heartbreaking to hear that. To know that she needs to return to survive. Ultimately the God who sees wants her survival so that she can find liberation both for herself and for Ishmael. God isn’t going to fix this but will offer companionship in the heartbreak.

The idea of God coming alongside, of being Hagar’s companion in her darkest moments made me thing about the work of a pastor who worked with unhoused people in Seattle. He’s retired now, but Craig Rehnebohm developed the idea of mental health chaplaincy in his work with folks in Pioneer Square and downtown. And one of the primary tools that he used in reaching out to people at the intersections of mental health crisis and homelessness was what he called companioning.

When I heard it explained to me years ago, the image that was used was literally sitting or standing or maybe even walking a little ways beside. This was a literal approach to take with folks – non-confrontational and open, allowing for an exit – but it’s also an attitude in relationship. Facing the same direction we see and experience something of the world of the other. We can offer support. We can listen without needing to debate or fix.

I wonder if – even though I might really want God to be a liberator – God is more often coming alongside as a companion. Especially in these Hebrew Bible stories, the lives of the ancestors are as complicated as our lives are now. There may not be a lesson, or a neat ending.

In among that complicated story, where is there a kernel of good news? Where is there invitation? I believe it’s in God alongside. God as companion to the one most vulnerable, most harmed. God who sees. I believe God comes alongside each of us in our crisis and is inviting us to do the same. Offering what we can for the time that we can. May we see God with us and be God in the world. Amen.

—